Living in the epicenter of the coronavirus plague is a surreal experience. Outside my window, New York City appears serene – devoid of its former noise, bustle, and loud citizenry. However, a few blocks north, south, and east it is a war zone with fatalities piling so high that administrators are utilizing mass graves. One of the most maddening images of the early days of the crisis was seeing nurses wearing Hefty garbage bags as Personal Protection Equipment (PPE).

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Congress passed the 1941 Fifth Supplemental DoD Appropriations Act which mandated that all military uniforms be manufactured domestically citing national security. In 1952, this Act was expanded and renamed The Berry Amendment, requiring the Department of Defense “to give preference in procurement to domestically produced, manufactured, or home-grown products, most notably food, cloth, fabrics, and specialty metals.” Tragically, even after past global epidemics (e.g., H5N1, SARS, MERS, and Ebola) the Federal Government failed to expand The Berry Amendment to include medical supplies to prepare for the next global pandemic.

In November 2005, President George W. Bush issued a “National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza,” in response to the outbreak of the Asian Avian Flu. Thirteen days later, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Peter Pace followed up by establishing his own “Planning order directing all combatant commanders to conduct execution-level planning for a DoD response to pandemic influenza… Develop a contingency plan that specifically addressed the three major missions of force health protection, defense support for civil authorities, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.” In parallel with the military preparedness, the White House signed an executive order to deploy more than $7 billion in developing vaccines, therapies, quarantine strategies, and hospital readiness in combatting the potential pandemic. These efforts contained the virus in the early days and potentially saved thousands of American lives. The contrast to today’s reality could not be starker in the rationing of PPE for the warriors on the frontlines.

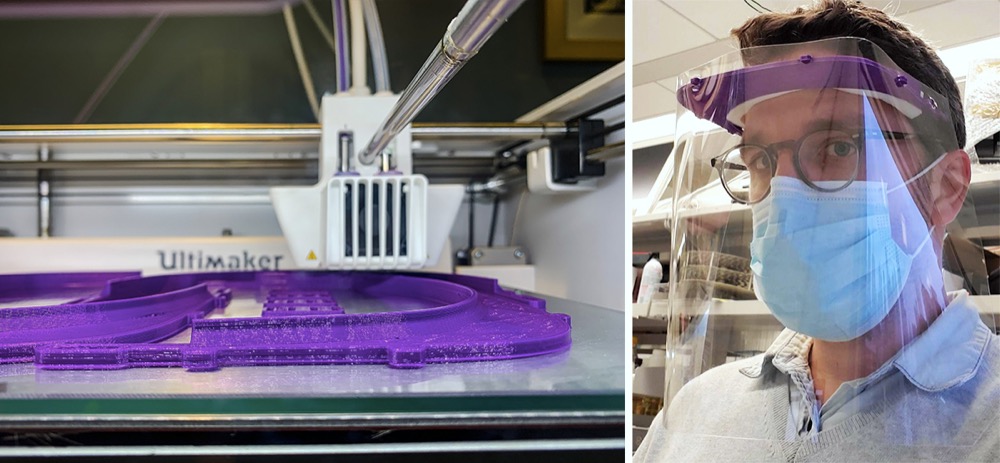

Some of the most inspiring moments during the current morass have been witnessing ordinary people joining together to deliver food to quarantined seniors; ordering pizza and cookies for overworked emergency crews, and hardware inventors manufacturing PPE with 3D printers. Across the country, entrepreneurs have utilized their ingenuity to fill in the gap of government shortfalls. A few weeks ago, I was introduced to one such innovator, Greg Brittingham, a Ph.D. candidate at NYU Langone (one of New York City’s hardest-hit hospitals). The cell biologist turned automation maven quickly joined a grassroots effort to produce face shields for medical professionals across the Big Apple. Recently, I interviewed him as part of my series on how engineers are joining the fight against the deadly virus with robots.

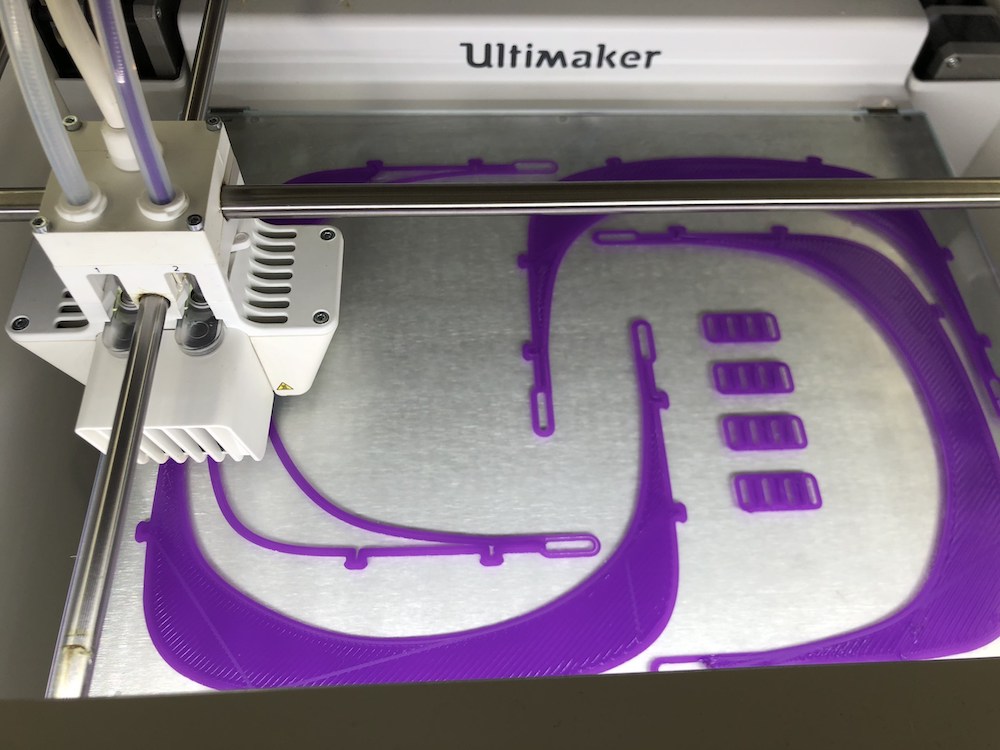

Brittingham is currently a student at The Institute for Systems Genetics at NYU Langone Health (ISG). The head of ISG, Dr. Jef Boeke is famous for creating synthetic DNA out of baker’s yeast. “The ISG is a research institute at the hospital that takes a systems approach to understand fundamental biological principles and human disease,” explains the young research assistant. Brittingham describes his familiarity with robots and additive manufacturing from working in the institute, “Building megabase scale DNA requires many steps. To make this process more time-efficient, our institute has a suite of robotics and automated liquid handles as well as 3D printers to build custom lab tools.”

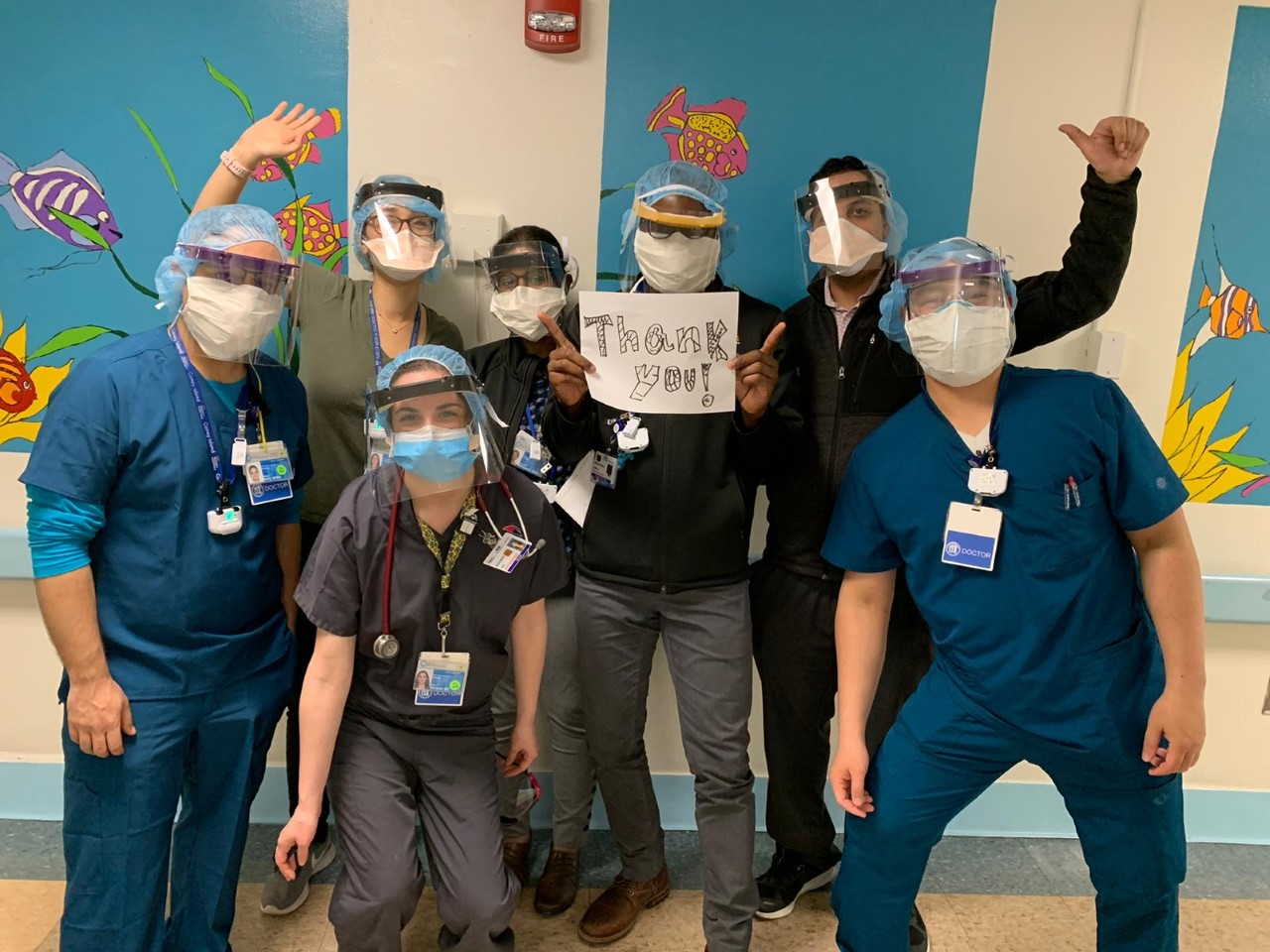

As someone thrown into the trenches, I asked Brittingham to characterize his experiences at the hospital during the current situation. “Our entire medical system is working overtime to fight this thing. They are exhausted emotionally and physically, but they are fighting on. I think the most important thing we can do for them is to make sure they feel safe and appreciated.” He added, “Having proper PPE is a huge part of that, but so are the little things like sending food to doctors and nurses on the frontlines.” While he couldn’t treat patients, Brittingham along with his fellow researchers are using the lab’s equipment to manufacture PPE for the entire metro area.

The NYU graduate student recounts the origins of the endeavor, “Tim Lionnet (an assistant professor at the ISG) and Ben King (a post-doc in Tim’s lab) conceived of the 3D printed face shield initiative in mid-March after a discussion with Michael Pacold (a physician-scientist who understood the upcoming challenges hospital systems in NYC would be experiencing). They reached out to the team of people with expertise in 3D printing at the ISG including Andrew Martin, Neta Agmon and myself and we started prototyping designs and optimizing print times. We set a goal of producing hundreds of face shields a day, but found that with the 3 printers in the medical center we could only print ~ 50 shield holders a day.” He continued chronicling how this internal movement grew outside the institute, “In order to print more shield holders we needed to tap into a broader network of printers and we have been amazed at how enthusiastically the NYC printing community has responded. We reached out to our network who made further introductions and we were able to build a cohort of over 20 sites including the NYU Tandon School of Engineering (Victoria Bill, Christina Lafontaine, and Elizabeth New), the Department of Biomaterials at NYU College of Dentistry (Lukasz Witek), Ryan Brown at NYU Langone Radiology, Doug Larson at Graft Milk (a custom matte filament company), Drew Hamilton at NYU tech4health, Marcus Swagger of Future Space NYC, Carlos Carmona-Fontaine and Logan Schachtner at NYU Biology Downtown, Lionel Christiaen at NYU Biology Downtown, Alexander Susse at the New Lab, Matt Griffin at Ultimaker and personal printers across the city, in upstate NY, NJ, CT and even a printing group in Chicago that Doug Larson reached out to.”

Once the machines were in place, the face shield crew sought out people to produce and deliver the goods. “Additionally, we needed volunteers to assemble the face shields and coordinate pickup and delivery across the city. We have had over 70 volunteers from the Sackler Graduate School for Biomedical Sciences and the Post-Doc Association at NYU Langone. With the help of all of these volunteers we were able to hit our goal of 200 shields assembled and delivered every day,” boasts Brittingham. He further expounds that in the last two weeks the team has donated over 1,600 shields across the city, including NYU Langone (Radiation Oncology, Periop, Gastrointestinal, Emergency Management, Cardiology, Anesthesiology, Breast Oncology), NYU Winthrop (Dental), SUNY Downstate (including Pediatrics), Elmhurst, Mt. Sinai (GI, Neuro ICU), Montefiore/Einstein, Weill Cornell, Brookdale, Harlem, Woodhull, NYP Methodist Brooklyn, and Ridgewood Volunteer Ambulance Corp. Brittingham is most proud of the fact that the “shields are comfortable to wear, easy to see through and re-usable (so long as there are cleaning supplies which we have also been trying to provide).” He plans on shipping the face shields to other localities if the need arises.

I nudged Brittingham for his thoughts on expanding internal 3D printing and automation programs nationally, post-conflict. “The fact that this pandemic started in the manufacturing hub of the world’s largest manufacturer, adds to the problem. That is why self-assembly has played a crucial roll in filling that supply chain gap,” he reflects. “Unfortunately, there were no hospitals in the US that had enough PPE stockpiled to battle the coronavirus. The issue is that even if you have enough PPE to protect the people on the frontlines there are many other departments that are still seeing patients. As the pandemic spreads, patients coming in for entirely unrelated diseases are also infected with Covid19,” cautions the Ph.D. student. He sums it up succinctly, “I think that this entire pandemic has taught us that having local manufacturing capabilities is a life-saver when traditional manufacturing can’t fill the need for medical supplies. I think that these trends will become more widespread after this pandemic – while local 3D printers aren’t going to replace a traditional supply chain any time soon, they provide a stopgap that can produce critical medical materials in a time of need such as this. I don’t know if hospitals will expand these capabilities but I can tell you that it is relatively easy to make, and the people on the frontlines love them.”