Recently, private equity giant Blackstone Group announced the acquisition of Colony Capital for $5.9 billion, a deal that encompasses 60 million square feet of warehouse space across 465 facilities. Blackstone is reported to manage now over $250 billion worth of property worldwide, and the Colony purchase comes on the heels of previous warehouse acquisitions of Singapore’s GLP and Gramercy Property. This latest portfolio of fulfillment centers puts Blackstone in control of more than 440 million square feet of distribution centers. This week logistics competitor Prologis purchased Liberty Property Trust for $12.6 billion, enabling them to now manage over 570 million industrial square feet. In explaining the aggressive move, Blackstone President Jonathan Gray said, “We’ve been the big buyer of warehouses around the world, probably bought $70 billion, on the simple premise that goods are moving from physical retail to online retail.” Probably the best (and most ironic) realization of Gray’s strategy is the recent moves by Amazon in converting closed malls across the country into fulfillment centers.

As more stagnant real estate is transformed into bustling e-commerce hubs, hiring skilled labor is becoming increasingly more challenging. In the words of labor-management executive, Peter Schnorbach, “It used to be that every month, businesses would get rid of their bottom 10% and replace them with new people. That doesn’t work anymore, because you can’t replace them.” Ever since its buyout of Kiva Systems, Amazon has been actively transforming its workforce from human hands to mechanical ones. Today, the trillion-dollar company employs more than 100,000 robots at 175 distribution centers nationwide. According to labor statistics, the retailer’s seasonal staff in 2016 and 2017 was 120,000 and 150,000 workers, respectively. In 2018 that number dropped to around 100,000 and many predict it could decline further in 2019, even though this year’s holiday online spending is estimated to soar to over $140 billion (up 14%).

Besides reinvigorating shuttered shopping centers into vibrant commerce depots, Amazon has been investing significant dollars in incubating exclusive mechatronic inventions. Yesterday it announced the investment of $40 million in constructing a new 350,000 square foot “robotics innovation hub” in Westborough, Massachusetts. The press release boldly declared the industrial building as the “company’s epicenter of robotics innovation.” Tye Brady, Amazon Robotics’ Chief Technologist, explained that the new structure will be able to consolidate all its automation labs and manufacturing floors into one destination that will “design, build, program, and ship our robots, all under the same roof.” For years, the e-tailer hosted “picking challenges” inviting roboticists from around the globe to compete in solving the company’s hardest fulfillment problems. Last year the annual event mysteriously disappeared and reappeared as an online platform for submitting grant proposals of scientific research (enabling Amazon a first look at the latest academic breakthroughs).

In the world of corporate innovation, there is theater and then there is hands-on development. In the former, the innovation department is typically housed in a beautifully architected showroom appointed with the latest gadgets complete with enthusiastic collegiate demonstrators. Unfortunately, there are too many of these corporate actors eagerly playing the role of technology scouts for the understated real purpose of publicity. Jeff Bezos’ company operates in opposition to these stage productions. The best illustration of the Amazon model is the launch of the $100 million Alexa Fund in 2015 to accelerate the ecosystem for its Echo speaker. While Apple’s voice application, Siri, released in 2011 in millions of iPhones, Alexa quickly became the de-facto home voice assistant with over 100,000 million units shipped with 70,000 voice-enabled skills. Today more than 150 products have Alexa built-in and more than 28,000 smart home devices work with Alexa made by 4,500 manufacturers. The key to this strategy was recognizing the impact of the development community and their fresh perspective to innovate in new creative ways beyond the original design. As a further testament to its success, the Alexa fund has grown to $200 million to expand its “Alexa Everywhere” goal. As Brady’s team aims to fill the Westborough property with the latest robot advances, a similar fund model could be adopted to outpace Walmart, Walgreens and other retailers that have recently upped their innovation game. In June, Walmart hired Scott Eckert, formerly of Rethink Robotics, to run its “Next Generation Retail” division out of its New Jersey incubator Store No. 8 and Walgreens last January teamed up with Microsoft.

As an early-stage investor, I am inundated daily with pitches that overstate their sales by bragging their list of pilot engagements. Astute managers know too well that turning these proofs of concepts into recurring revenues is a long arduous road that requires significant capital and time to generate success. To guide founders through this process, I coach them on aligning their pilots with the revenue milestones of their prospects. While Amazon, Walmart and other large retailers are able to budget large outlays to automate their warehouses, the majority of America’s operators find robotics unapproachable as the unit economics still exceed the annual salary of their workers. While long-term machines could operate continuously (without healthcare and workers compensation) in reality Robo-deployments require additional investments in ongoing maintenance, physical plant upgrades, and staff training. Rather than promoting machines as an outright replacement to hourly wages, installations should be tied to increasing worker output to multiply revenues to escalate fulfillment.

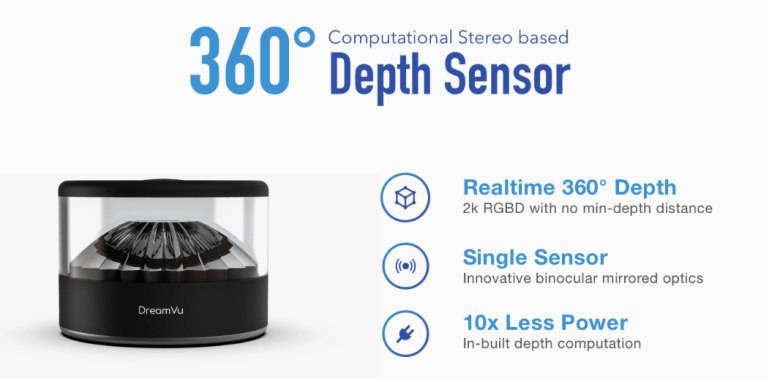

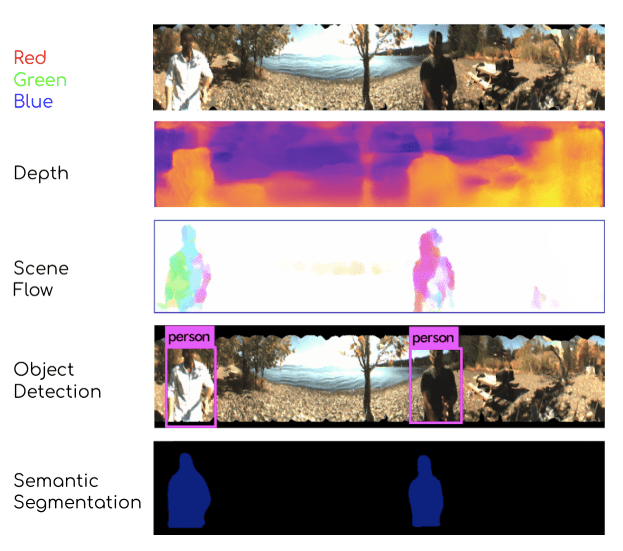

As a mentor of the Deep Tech track at New York University’s Endless Frontier Labs, I have met with two startups which are focused on developing technologies to bring down the unit economics of automation – Wheel.me and DreamVu. Three weeks ago, I detailed wheel.me’s motorized castor that potentially transforms any wooden pallet into an unmanned system. This week I interviewed Rajat Aggarwal, Chief Executive, of DreamVu who has developed a 360-degree vision sensor, named PAL, priced at a fraction of the cost of other available sensors. Aggarwal describes how his invention is already changing the financial model, “Currently, sensing is a bottle-neck for scaling. We felt a strong need for such a vision sensor, which can eliminate the requirement of multiple sensors. Autonomous navigation in highly cluttered and dynamic environments, teleoperation, and situational awareness are key applications where PAL is best suited.” Unlike autonomous vehicles that utilize GPS, indoor robots rely solely on sensors to navigate around their environments. To date, unmanned rovers moving cartons around the warehouse have been weighted down with expensive sensors to capture its spacial understanding within the facility to avoid collisions with humans and other equipment.

In comparing his solution to other offerings Aggarwal boasts, “PAL introduces a multifold advantage in terms of cost, compute, and power requirements over other competing sensing technologies.” While many of the existing robot installations rely heavily on LiDAR-enabled navigation, which cost thousands of dollars per sensor, he believes that these devices are “overkill, given their high price points, longer ranges, and overwhelming precision.” In order to roll out automation on a mass scale, integrators need to “focus on manufacturability, scalability, and ability to operate in the world designed for humans.” The technologist further claims, “To enable complete autonomy, we need situational awareness, which is not just complete but also very fast. And we have to scale this sensing for the millions of these robots; the sensing cost has to go down. DreamVu’s optics technology simplifies the way we are used to capturing different types of data (2D images, 3D images, 3D point clouds) and then fusing this data to a complex and heavy AI engine.”

Today’s logistics market is a forerunner for other segments of autonomy. Aggarwal shared his long-term outlook, “79 million (people) will have a robot inside their homes by 2024. These robots will need to operate autonomously in homes, which are cluttered and dynamic environments. 360° depth-sensing would be very critical. There is no other solution in the market that will be able to provide the required output at the given price point (<$50) and hardware specifications.” He continued, “In the next 5 years, we see ourselves entering the drone, smart home, smartphone, and endoscopy market, providing affordable 360° sensing in all cases. We have an upcoming product with ultra high resolution and higher depth ranges, which can work in both indoor and outdoor environments. We are already doing early pilots in the smart city (retail, building) and smart surveillance use-cases.” Rather than pitching investors with a collage of corporate logos, Aggarwal is following the path of Amazon by empowering the developer community with powerful tools, “Our customers are thrilled to see a new approach to surround sensing that they can try out with our evaluation kits, which are available to order. The seamless hardware and software integration allows them to test the sensor very quickly and reduces product development time for them.” The entrepreneur optimistically predicts, “If the sensing is done right- the AI will be more accurate, and hence a robot would be more efficient and robust.” This holiday season DreamVu, and a fleet of other technologies will be making its warehouse debut – enabling pickers to pack orders at record-breaking speeds (and profits).