Earlier this month, I crawled into Dr. Wendy Ju‘s autonomous car simulator to explore the future of human-machine interfaces. Dr. Ju recently moved to the Roosevelt Island campus from Stanford University. While in California, the roboticist was famous for making videos capturing people’s reactions to self-driving cars using students disguised as “ghost-drivers” in seat costumes. Professor Ju’s work raises serious questions of the metaphysical impact of docility.

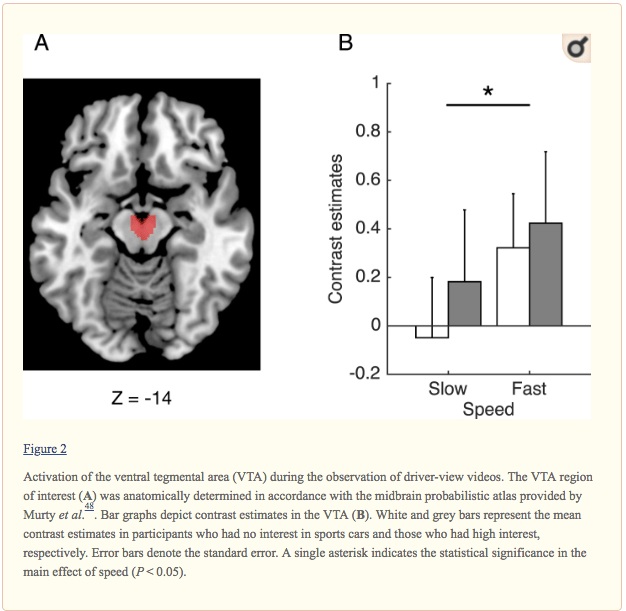

Last January, Toyota Research published a report on the neurological effects of speeding. The team displayed images and videos of sports cars racing down highways that showed spikes in brain activity. The study states, “we hypothesized that sensory inputs during high-speed driving would activate the brain reward system. Humans commonly crave sensory inputs that give rise to pleasant sensations, and abundant evidence indicates that the craving for pleasant sensations is associated with activation within the brain reward system.” The brain reward system is directly correlated to the body’s release of dopamine via the Ventral Tegmental Area. The findings confirmed that higher levels of brain activity on the VTA “were stronger in the fast condition than in the slow condition.” Essentially, speeding (which most drivers engage in regardless of laws) is addicting as the brain rewards such aggressive behaviors with increased levels of dopamine.

As we relegate more driving to machines, the roads are in danger of becoming highways of strung out dopamine junkies craving new ways to fill their fix. Self-driving systems could lead to a marketing battle for in-cabin services pushed by manufacturers, software providers, and media/Internet companies. As an example, Apple filed a patent in August for “an augmented-reality powered windshield system,” This comes two years after Ford filed a similar patent for a display or “system for projecting visual content onto a vehicle’s windscreen.” Both of these filings, along with a handful of others, indicate that the race for capturing rider mindshare will be critical to driving the adoption of robocars. Strategy

Analytics estimates this “passenger economy” could generate $7 trillion by 2050. Commuters who spend 250 million hours a year in the car are seen by these marketers as a captive audience for new ways to fill dopamine-deprived experiences.

I predict at next month’s Consumer Electronic Show (CES) in-cabin services will be the lead story coming out of Las Vegas. For example, last week Audi announced a new partnership with Disney to develop innovative ways to entertain passengers. Audi calls the in-cabin experience “The 25th Hour,” which will be further unveiled at CES. Providing a sneak peak into its meaning, CNET interviewed Nils Wollny, head of Audi’s digital business strategy. According to Wollny, the German automobile manufacturer approached Disney 18 months ago to forge a relationship. Wollny explains, “You might be familiar with their Imagineering division [Walt Disney Imagineering], they’re very heavy into building experiences for customers. And they were highly interested in what happens in cars in the future.” He continues, “There will be a commercialization or business approach behind it [for Audi]… I’d call it a new media type that isn’t existing yet that takes full advantage of being in a vehicle. We created something completely new together, and it’s very technologically driven.” When illustrating this vision to CNET’s Road Show, Wollny directed the magazine to Audi’s fully autonomous concept car design that “blurs the lines between the outside world and the vehicle’s cabin.” This is accomplished by turning windows into screens with digital overlays that simultaneously show media while the outside world rushes by at 60 miles per an hour.

Self-driving cars will be judged not by the speed of their engines, but the comforts of their cabins. Wollny’s description is reminiscent of the marketing efforts of social media companies that were successful in turning an entire generation into screen addicts. Facebook founder Sean Parker, admitted recently that the social network was founded with the strategy of consuming “as much of your time and conscious attention as possible.” To accomplish this devious objective, Parker confesses that the company exploited the “vulnerability in human psychology.” When you like something or comment on a friend’s photo, Parker boasted “we… give you a little dopamine hit.” The mobile economy has birthed dopamine experts such as Ramsay Brown, cofounder of Dopamine Labs, which promises app designers with increased levels of “stickiness” by aligning gameplay to the player’s cerebral reward system. Using machine learning Brown’s technology monitors each player’s activity by providing the most optimal spike of dopamine. New York Times columnist David Brook’s said it best, “Tech companies understand what causes dopamine surges in the brain and they lace their products with ‘hijacking techniques’ that lure us in and create ‘compulsion loops’.”

The promise of automation is to free humans from dull, dirty, and dangerous chores. The flip side many espouse is that artificial intelligence could make us too reliant on technology, idling society. Already, semi-autonomous systems are being cited as a cause of workplace accidents. Andrew Moll of the United Kingdom’s Chamber of Shipping warned that greater levels of automation by outsourcing decision making to computers has lead to higher levels of maritime collisions. Moll pointed to the recent spat of seafaring incidents,”We have seen increasing integration of ship systems and increasing reliance on computers. He elaborated that “Humans do not make good monitors. We need to set alarms and alerts otherwise mariners will not do checks.” Moll exclaimed that technology is increasingly making workers lazy as many feel a “lack of meaning and purpose,” and are suffering from mental fatigue which is leading to a rise in workplace injuries. “Seafarers would be tired and demotivated when they get to port,” cautioned Moll. These observations are not isolated to shipping, the recent fatality by Uber’s autonomous taxi program in Arizona faulted safety driver fatigue as one of the main causes for the tragedies. In the Pixar movie WALL-E, the future is so automated that humans have lost all motivation to leave their mobile lounge chairs. To avoid this dystopian vision, successful robotic deployments will have to strike the right balance of augmenting the physical while providing cerebral stimulation.