Memphis at 1 am is quite possibly the busiest airport without passengers on the globe. Touring the 880 acre FedEx facility, I marveled at the speed and efficiency of the automation technologies that can process close to a half a million shipments an hour and 250 flights a day. The cargo hub is a shining example of the synthesis of humans and machines. This past March, FedEx announced it is ratcheting up its commitment to augmenting employees with mechatronics. David Cunningham, FedEx’s CEO, explained the motivation behind its new billion-dollar renovation of the $62 billion nerve center, “We will be investing in new sort systems, new automation, new capabilities, modernization of the facility, expanding our truck and unload capabilities here substantially but we’re also going to be making this a much better place to work for our employees.”

Driven by the insatiable appetite of online shoppers, FedEx is exploring new ways to increase capacity to keep up with demand. Almost concurrent with Cunningham’s announcement, the New York Times reported on how the shipper is using Vecna’s autonomous “tuggers” or rovers to move odd-shaped cargo through its North Carolina distribution center. While a handful of jobs could be lost as a result, the increased capacity is on track to add a 100 new jobs a year. Galen Steele, FedEx senior manager at the North Carolina facility, remarked, “I understand people thinking this will take their jobs. But over time, they realize that is not the case at all… Everyone will have a job. It just might be in a different place.” As I watched purple-clothed sorters busily unload boxes onto conveyer belts and reload them into airplane-ready containers, I reflected on Steele’s statement asking myself if it would still hold weight if (or when) FedEx deploys humanoids?

I understand people thinking this will take their jobs. But over time, they realize that is not the case at all… Everyone will have a job. It just might be in a different place.

Conveyor belts, scanners, and even autonomous rovers are ultimately built to maximize employee output, but humanoids are expressly created to replace humans. Last year, Boston Dynamics awed the tech world with the acrobatics of Atlas. Since then, the company was purchased by SoftBank. Last May, at The Robotics Summit in Boston, Marc Raibert, founder of Boston Dynamics, demonstrated to a packed crowd the commercial aspects of its robotic dog SpotMini which is expected to be available for purchase next year. One of the earliest use cases touted by Raibert is last mile delivery, as the ability of his robotic dogs and humanoids alike, to climb and navigate unstructured environments is unparalleled. In addition, SoftBank has promoted for years its interest in humanoids with its own line of Pepper robots. According to the company, Pepper is currently operating in more than 2,500 places, including retail stores, bank branches, hotels, museums, airports, train stations, offices, hospitals, and nursing homes. Raibert could finally have the right partner in place to not only fulfill his long-term goal of making “robots that have mobility, dexterity, perception, and intelligence comparable to humans and animals, or perhaps exceeding them,” but even more aptly the ability to cost-effectively mass produce and distribute them globally.

Nowhere is the humanoid question more debated than in Japan. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Japan’s estimated population fell by a record-breaking 264,000 people in 2017. There are three factors affecting the decline: 1) low-birth rates, 2) anti-immigration policy, and 3) growing elderly population. Currently, a third of the republic’s population is over 65, with deaths outnumbering births by an average of 1,000 people a day. Its labor force is dropping even faster, projecting to plummet by 24 million workers over the next thirty-two years. For decades Japan has been a powerhouse for manufacturing industrial robots accounting for a third of the $6 billion sales in 2017, led by FANUC, Kawasaki, Sony, and Yaskawa. The government of Japan envisions an even more robotic future of replacing its dying citizens with machines, particularly humanoids, to maintain its current standard of living and care for its geriatric citizens.

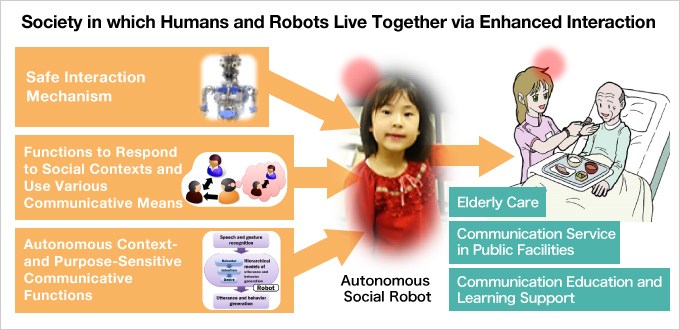

Although recently social robotics in America has seen the demise of Jibo and Kuri, in Japan there is an explosion of activity. At Hiroshi Ishiguro Laboratories (HIL), Hiroshi Ishiguro is researching “Symbiotic Human-Robot Interaction” with the expressed goal of creating “autonomous social robots that can communicate with multiple humans.” Ishiguro has already developed a number of life-size androids, including one after himself, complete with artificial: skin, hair, speech, intelligence, and contextual understanding. For example, Ishiguro’s androids have the ability to of deciphering conversations of multiple people to create “hierarchical models consisting of desire, intention, and behavior.” In a recent USA Today article profiling their latest model, Erica, Takashi Minato, lead HIL researcher, describes immediate societal applications: “In Japan, many are living alone, and they need to have a conversation with others. The human-like robot can help support them.” The unveiling of Erica, which conjures up disturbing images of West World, is on the heels of Hanson Robotics gaining citizenship for its Sophia cyborg in Saudi Arabia.

While Sophia now has a passport to travel, she still can’t walk. Understanding the shortcomings of humanoids is not cognitive but gait, Agility Robotics recently raised $8 million to bring robotics legs to the market. In the press release, the startup boasted “Agility Robotics is solving the mobility problem faced by mobile robots, to allow machines to work with humans, for humans, and around humans. Robotic legged locomotion will enable a major transformation of our world, with applications in logistics and package delivery for fast and inexpensive 24/7 service, in-home robots for telepresence and assistance, and real-time data collection and mapping of human and natural environments.” As a further endorsement of Agility’s value proposition, the financing round was led by Andy Rubin’s Playground Global. Rubin formerly headed up Google’s robotics division that acquired over 10 robotic and AI companies in 2013, including Boston Dynamics that was later sold to SoftBank. In describing the immediate applications for Agility, Playground’s co-founder partner Bruce Leak said, “We wanted to focus on solving mobility in areas where wheeled platforms can’t reach (i.e., stairs, curbs, etc) and legged systems are best suited to address—opening up opportunities to solve the last 100 feet rather than the last mile.” Crossing the threshold of those last 100 feet could finally open the door for humanoids empowered with such bipedal locomotion to navigate our society.

We wanted to focus on solving mobility in areas where wheeled platforms can’t reach (i.e., stairs, curbs, etc) and legged systems are best suited to address—opening up opportunities to solve the last 100 feet rather than the last mile.

According to ResearchAndMarkets.com the global humanoid market is projected to exceed $25 billion over the next decade, driven by the “growing adoption of all types of human-like robots in a magnitude of industrial applications across the globe.” While this aggressively optimistic report has given rise to a number of teams starting commercial endeavors across the ecosystem, in recent months the industry has also seen the cessation of Honda’s Asimo. The loss of Honda’s investment could be a catalyst to propel new entrepreneurs into the spotlight, similar to the early days of the personal computing era when the greatest minds of Bell Labs moved to California to launch their own semiconductor startups. As Bill Gates predicts: “There will be more progress in the next 30 years than ever… Once computers/robots get to a level of capability where seeing and moving is easy for them then they will be used very extensively.”

Reprinted by permission.